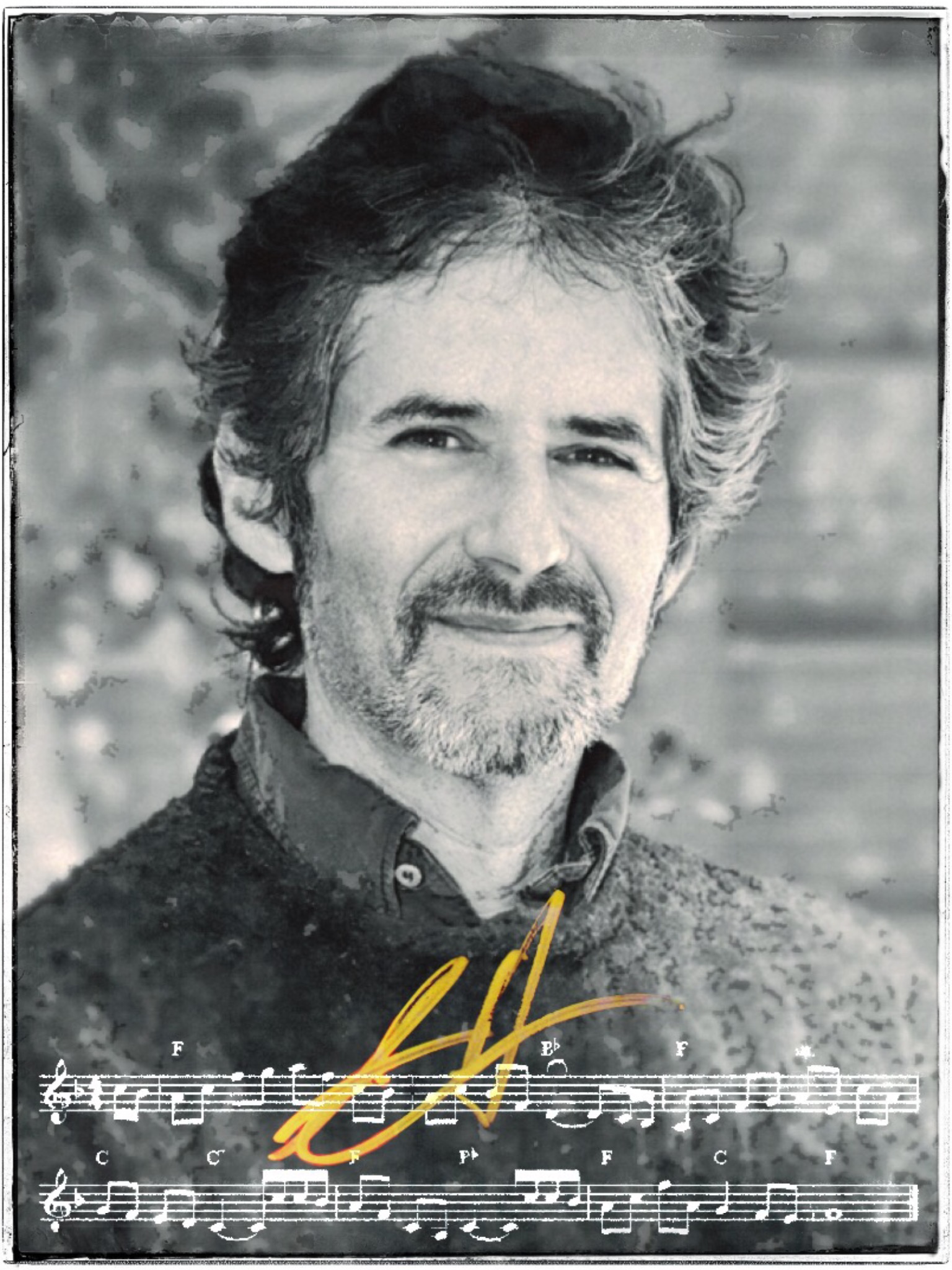

James Horner, the artist I most respect and admire in the world, died last week while pursuing his passion for flight. I struggled to gather my thoughts at the shock of this event. Below is that struggle—in the rawest and most personal post I've ever written...about this most personal loss. If it doesn't make sense...listen to the music.

Listen to the music...

-Brendan (July 1, 2015)

___________________June 23, 2015

August 14, 1953 — June 22, 2015

James Horner.

I have listened to his music every single day since 1997. And I have known it for all of my life.

The news of his death in an airplane crash. Impossible. I still can't believe it. I am reeling. I cried for a solid hour. Naomi held me. I have not felt this way since the loss of my father.

Horner is the most influential artist on my life. One of the most influential people in my life. There is no writer who comes close. No musician or filmmaker. His music has been the music of my life. It's been there in moments of great excitement and hope. In moments of desolation and despair. In moments of exploration and discovery. In moments when no other soul has been there. It has been a friend and a guide and a mentor and an inspiration.

I can't think of another person in history who has meant so much. The pain is so great.

I knew that this day would come. I just didn't know it would be so soon.

James Horner. Gone. In pursuit of the heavens.

His music is here. His music and his spirit will never die. And suddenly every note feels so much more personal.

But his music is not all about loss. He was not all about loss. His music is a celebration of life and of nature. Of this world.

I am so immeasurably lucky to have his music in my life. Forever.

When I was younger I knew that one day bad things might happen. But I would always have this music. And nothing could ever take it away. Not failure or loss or death.

There is very little in life that is permanent. But this music is as permanent as the firmament.

He gave so much—so much more than any creative artist or person I have ever known. I can never even come close to his contribution. It is an inspiration. It is the very fabric of my world. And it is not torn or tarnished today—but rings with a new strength.

There are scores yet to come. We await the music from his aviation documentary. From the film Southpaw and the film The 33. We await a recording of his concerto for four horns. And there is the rejected score for Romeo and Juliet out there somewhere. And all of the work that has gone unpublished...This year alone we will have seen:

- Wolf Totem

- Pas de Deux

- Living in the Age of Airplanes

- Southpaw

- The 33

- Concerto for Four Horns

These albums alone could make a career in music.

And what would Horner say? What does his work say?

Think of the heart; of the love at the center of the story. Listen to the sounds of nature, explore the forest, and hear the mist move on the ocean. Touch the clouds. See the world from 30,000 feet, and hold those you love close. Be bold in your passions. Fall in love.

A tribute. I have always dreamed of sharing my love for Horner's music in a musical essay of sorts. An audio essay. I wonder if now is the time to do this. To trace the development and the themes and the heart of the music. To touch on what it's meant to me. Or to simply feature the artist in his own words, describing his work...

I must consider this project very closely. What direction it should take.

"The music of cinema has lost one of its great creative lights with the passing of James Horner. James’ music was the air under the banshees’ wings, the ominous threat of approaching aliens, and the heartbeat of TITANIC. We have lost not only a great team-mate and collaborator, but a good friend. James’ music affected the heart because his heart was so big, it infused every cue with deep emotional resonance, whether soaring in majesty through the floating mountains, or crying for the loss of loved ones in the frigid waters of the Atlantic. James Horner stands with a handful of the grand masters of cinema music. We will miss his humor and intelligence, his genuine warmth as a human being. And we will miss the music that never gets written now, the scores we will never hear. But James' heart will go on, in his music, which lives within so many films that will never be forgotten. Thank you, James. Fly brother."

— James Cameron & Jon Landau

"James Horner was a rare artistic genius. He did not merely augment the image he was presented with, he was able to transcend its matter and logic & travel straight to the heart and soul with his magical gift … a gift that truly reflected his own heart & soul. I will miss him."

— Mel Gibson

- Schubert lived to 31.

- Mozart lived to 35.

- Gershwin lived to 39.

- Mahler lived to 51.

- Beethoven lived to 57.

- Respighi lived to 57.

- Horner lived to 61.

"It is important to note that Horner died engaged in something he loved. He followed his heart’s passion and that’s a valuable lesson for us all no matter what the consequences of that pursuit may be."

— ScoreKeeper

"I am raw, I bleed, I do not sleep well. I am angry! I struggle to find a path forward...I cannot accept this. This is not right. . . I will never be the same."

— Craig Richard Lysy

"Why write today? This day does not exist. This day is a nightmare and I want to wake up."

— Jean Baptiste Martin

“I saw Apollo 13 when I was 13, which will have been 20 years ago exactly, next Tuesday. It was a seminal moment for me. I wouldn't be me without him.”

— TheGreyPilgrim

"Today will have me listening to nothing but the man that took off in his plane, but never landed (for me he is still soaring above there somewhere, for all eternity)."

— DreamTheater

"Without James there is no 'me.'"

— Conrad Pope (orchestrator, collaborator with Horner)

"No words. My sadness is so deep that it is difficult to process. Perhaps God needed someone to help write His music. Godspeed Maestro."

— John Debney (composer)

"What a sad day for all of us. A great composer gone - and with him the world will be a little less beautiful, less soulful. We lost an artist that everyday created music that touched our hearts and souls, invented memories for us to share and who's music brought us closer together. James, we miss you."

— Hans Zimmer (composer)

"I think some people are satisfied living vicarious adventures through film, and I think he and I were attracted to real adventure.”

— James Cameron

"There's a sense in which the composer of an old-fashioned orchestral score could almost be considered the second, shadow director of a film—the one who's putting the finishing emotional touches on the movie and also sometimes perhaps suggesting what the film is supposed to be, even if for whatever reason that's not coming through without the music. I get the impression that Horner did that a lot..."

— Matt Zoller Seitz

"James Horner's music is the sound of an absence made present. It is the sound of a bond that by all rational accounts should be severed but is saved by the depth of its impression on memory."

— Sophie Monks Kaufman

"The subtext of almost everything he did, even something as concentrated as Searching for Bobby Fischer is a sort of generalized astonishment at being able to see and hear things and think about them."

— Matt Zoller Seitz

"James Horner was not just a master composer, but one of the great modern American storytellers in any art form."

— Matt Brown

"Horner's skill at richly and romantically capturing the emotional language of personal transformation draws many of his best scores together."

— Matt Brown

"He was one of the most extraordinary dramatists of our time."

— Scorekeeper

"His music is eternal."

— Jean Baptiste Martin

"He seemed to be such a kind and well-spoken person. He really cared for the music, for the emotion that he wanted to evoke in the movie. He was a romantic with a huge heart."

— Mike (on Filmtracks)

"He was magical to work with, and I feel blessed that we had the opportunity to collaborate together.... We have lost a special soul who touched so many people through his art. Rest in peace my friend, you left us with the gift of your incredible music."

— Antoine Fuqua, director of Southpaw

"They say you should never meet your heroes, because they will never live up to your image of them. James Horner exceeded my expectations. He had a warm embrace and a smile that could light up a room. He devoted hours to talking with his fans. He had a solid, real respect for each and every one of us. He made us all feel like he was the one that was waiting in-line to meet us. A gentlemen, a genius and a wonderful human being. He will be fiercely and sorely missed, but his music and his smile will live on forever in every single person that he made cry, cheer, fearful, nostalgic, pensive, filled with utter joy, and stunned with dazzling wonderment."

— Lee Allen

"He spoke the language of the human soul."

— Scorekeeper

"I feel compelled to track down some albums that I don't own and bear witness to some of his beauties that lay undiscovered for me. It'll be painful, but the good kind then. I'll be appreciating and celebrating instead of grieving."

— Azulocean

"Perhaps his passion for flight was part of the sound we came to love and the two can't be separated."

— Karelm

"I asked him who his favorite film composer was: 'I have tremendous respect for John Williams. He is in a class by himself.' We then gushed over Williams’s output and evolution as a composer, citing case after case of terrific compositional cleverness and invention. I found James to be a true gentleman, a smart businessman, an excellent teacher, a sensitive artist with a big heart, and a composer who loved the art of collaboration—despite not always getting his way. In our final private meeting, I told him something I knew would be important for him to hear. When the composition area at UCLA interviews prospective undergraduate students in composition, one of the questions we often ask them is, 'Who are your favorite composers?' Expecting to hear Stravinsky, Schoenberg, or John Adams, to our amazement year after year the majority of applicants put James Horner at the top of that list. I saw a gracious, generous, sensitive but outgoing and humble man."

— Roger Bourland, Chair, UCLA Music Department

"I only met Mr Horner a few times and was privileged to attend some of his sessions. A very kind and intelligent man. Someone who cared deeply about those composers who came before. Very rare in Hollywood to meet someone who completely understood the art form he worked in. I met him shortly before I was heading to Europe to try my hand at conducting for the first time. He gave me some very encouraging words. Ran into him six months later and reminded him of our chat. Perhaps he was being polite but he claimed to remember me and inquired as to how my conducting turned out. I was honest and told him I’d leave it to more talented people as I was barely adequate. He laughed and invited me to another session after complimenting my efforts to broaden my understanding of music and the orchestra. I couldn’t attend those sessions and never saw him again. Glad I had the chance to meet a master. Hollywood will never see another James Horner and he will be sorely missed."

— Rick (at SlippedDisc)

"Man, what this guy could do! He led Achilles into battle, guided Alfred to redemption, ushered Eddie Murphy into stardom. He gave Balto his heritage, turned a cornfield into a baseball diamond and charged Fort Wagner. Yep. He rescued Jenny and made a champion out of Dre. Wow! This man found Spock! He almost got to the moon!! How many of us mere mortals can do that?? That's probably the difference. We're just mortals. This guy James Horner was... no, is immortal. His music will never stop."

— Doug Fake

"This is sad news indeed, and brings to mind what Grillparzer said of Schubert, ‘Here music has buried a treasure, but even fairer hopes.’"

— Hank (at SlippedDisc)

Thinking about this last night, I couldn't help but think about the place of the soul. Is it true that death truly is the end, or is there something beyond? I have always had my doubts—but have always been hopeful. I took solace in the quote at the beginning of a book I once read: that there is no such thing as destruction of matter. Everything is energy and no energy ever disappears. It is simply transformed and recycled. Why should we think then that the part that makes a person a person somehow ends? I wondered then—what is a life? What are we? And what of the soul? The thought that occurred to me last night was that perhaps the soul is everything that we have ever done—and will ever do. And that who we are at the moment is just the tip of the pen in the great story being scrawled out on the paper. Our soul is not in the pen—but in the words that were written—and that are yet to be written. In this way, it's so clear that Horner's soul lives in his music more than the man who died this week. He even said it himself: "write your soul." In this way, he is not gone. But lives as he always did: through the music that will live forever.

As a writer, this idea resonates. There is so much that I have written—so much that even I cannot remember. So many sides and colors of my own personality; that I could never carry it all with me in this eye-blink moment of NOW. I am not just this moment, but the sum of all of those past moments, and all of the moments yet to come. Not just the moments that I directly interact with, but that my actions and works have sparked. How, then, do you measure a life? Not by the individual, but by the collective works and passions of that individual. And Horner's work lives still.

Listening to Boy in the Striped Pajamas on Thursday now and I still feel like I'm living in an alternate reality. Like I got off on the wrong Universe—a Universe where Horner dies way too early. Where is the Universe that he's still alive? What is he working on right now? Where is he flying?

I see his name on the album covers and it doesn't seem possible. That name always stood for so much life—so much ...living, breathing, wind gently blowing through the garden.

I want to collect every piece of raw footage from every "making-of" film and put together a documentary. There are those making-of films out there. Three to five minutes each. But for each, think of how much unused footage, unused interview material was left on the cutting room floor. It must still be out there, right? Somewhere?

It’s been a few days now. A few have passed and here we are—on Saturday. Thinking of James Horner. That name, those words, when I see them, still have so much life in them. His work defined my life in so many ways that it’s impossible to see them now and to think that he is gone.

I’ve thought throughout this week that I should sit down and meditate on Horner’s impact on my life. What is that impact?

And yet, the perfectly formed paragraphs that I want to write are still impossible here. They seem so impossible with my mind still fractured by this crash. My thoughts scatter like leaves in a downdraft.

I have 58 hours of his music. Each hour takes me somewhere different. This isn’t music—it’s a passport to a new universe. Horner described his music as painting—and if he painted anything it was landscapes. Why landscapes, when his work was so emotional—so focused on the heart? Why not a portrait or a set piece? Because of how personal his music was.

If you think about it—portraits are always in third-person. You the viewer are expected to look on at some other person. To see their personality and the emotion on their face. A portrait is not a mirror, it’s a photograph—always at a distance…always with a space between.

But a landscape…a landscape is a window—it let’s you look through the eyes of another—to see another world and to make it your own. Horner’s music draws you in—surrounds you with the colors of another landscape. This time dark and split with shadows. This time bright and bubbling with green. This time swirling blue. Through Horner’s eyes we breathe underwater. Through Horner’s voice we hear the vacuum of space. He dismantles the walls, drops out the floor, and lifts you into the clouds—into a sky he knew so well. A sky that he saw in every light—painted by the burning embers a setting sun, or the purple depth of a rising storm.

He looked down on a world of noise and saw patterned there in the busy roads and sparkling roofs a geometry of stillness. He looked up beyond the sky to a void echoing in a space without walls. Suspended between two worlds, he now rises—leaving us behind but in his leaving, lifting us up to fill that void of his passage; lifting us up as he always did to see our world in a new way; and new worlds beyond that we could never see without him.

We are without him now, but not without his music. Everything he was to me still is.

58 hours of his music. How incredible is that? How exceptional in the history of music? How lucky I am that the musician whose work I fell in love with was so prolific? And I have fewer than 60 albums of his music. He wrote music for over 100 films.

All of Beethoven’s symphonies together are just about 6 hours of music.

All of Mahler’s symphonies together are about 11 hours of music.

All of the Beatles — 217 songs totaling about 10 hours of music.

Even a prolific folk hero like Bob Dylan…All of Bob Dylan’s written songs - about 521 total… [On “The Essential Bob Dylan” there are 32 songs across 2 albums totaling 2 hrs, 15 minutes of music—making each song on average about 4.18 minutes long.] That means the full catalog of Bob Dylan’s written songs is about: 2181 minutes or 36.5 hours of music.

I have 58 hours of James Horner’s orchestral work. And counting…

"It's all about interaction. There is no right note."

— James Horner

"The more I try ideas that are not normal ideas, the more I want them to know what I am doing up front. If you surprise someone at a recording session, you are going to have your score thrown out, it's human nature. You have to make them part of the process, and the more adventurous I become, the more I have them involved in the process."

— James Horner

“With three notes on the Uilleann pipe I could say more than 30 notes on the violin.”

— James Horner

"When you add the music, certain scenes that seemed like they were playing okay, suddenly go by way too fast. Because the music is like jet fuel. As soon as you add it—whump, and the sequence is gone."

— James Horner

"Perhaps there is a secret language of the soul, and Mr. Horner speaks it fluently."

— Henning Langen

“He's earned his position in the film scoring community, and there's no question — for me — that he's one of the most knowledgeable and capable composers who ever scored films. It was always great when I was working for Horner, because he'd go over a sketch and say, "This string passage here, you could probably treat it like Tchaikovsky did in his 4th Symphony, but maybe we should go with more of a Shostakovich approach." If I said, "But what about the way Holst handled the strings in the second movement of The Planets?" And he'd say, "Well, that's a little bit too direct for this." You can talk to him about music, and he's heard it and he knows what it's about...

Actually, I gained a lot of respect for Horner during Titanic, because Horner was accommodating Cameron in ways that I thought a composer the stature of Horner had no reason to accommodate anyone. He completely handled the situation with absolute humility and professionalism. I don't think there are very many composers who would have acquiesced to Jim Cameron the way Horner did. Horner gave Jim exactly what he wanted. I think there are some people who think that the Titanic score may be overly simplistic, or some people object to the Celtic nature of it, or whatever, but I can tell you that if any other composer had scored that picture, Jim would have fired him and at least four other composers before he got what he wanted. Horner was determined that that would not happen — and it didn't happen — and I think it was the best score that Jim would ever allow into that picture. For that reason, I think he deserves all the Academy Awards and accolades that he got...

There's a point where it becomes too much of an insult to bear. If a composer is very highly successful — and James Horner certainly is — that means that he has to take less of that kind of abuse than a composer who is not of that stature. From my limited vantage point, it seemed like changes were coming in just for the sake of changes to come in, and I was wondering — as I was picking up these changed sketches — why Horner was going to such lengths to make this guy happy. Once the film came out, I understood perfectly. That's another tribute to James Horner, because he has not only an amazing visceral insight into what a film needs musically, but he knows how these situations work and he knows when to do something and when not to do something. You've got to hand it to the guy.”

— Don Davis (orchestrator for Horner and composer of The Matrix)

One week after his death and I still can’t believe it. It still hurts to think about that moment when Naomi told me that he had died.

I’ve acquired his Jumanji score—one that I’ve never heard outside of the film. A great and very fun and actually quite moving piece of music. Most extraordinary: it has seeds in it of at least four scores that Horner would write afterwards:

- The Spitfire Grill - Many of the gentle moments from Jumanji are early versions of this score that he would write the next year. Surprisingly, one of the motifs that is so prominent in Spitfire Grill—a descending harp—is actually an echo of the extended theme from Jumanji that Horner uses later in the film.

- Titanic - In the track “Jumanji” at 4:47, the repeating horn in the distance is played—just as he would use following the impact with the iceberg in Titanic.

- Windtalkers - In the end credits, we hear the early vocal wailing almost verbatim that he would expand into whole tracks on the film Windtalkers

- Spiderwick Chronicles - The mysterious movements of Jumanji are obvious precursors to the magic he’d conjure in Spiderwick.

I must try to the think of Horner now as I’d think of a classical composer or an author from another time. One whose scope of work is set—but still as deep as the Mariana Trench.

Saying Horner is dead is like saying a part of me and my identity is dead. Like being left handed. Being left handed has shaped my worldview—made me feel aways a little different, a little set off from everyone else. As a child, this helped me to build my own space, to see the world differently from this different perspective. It shaped my identity so much. It would seem absurd if someone said suddenly: you are no longer left handed. Now you’re right handed. “But,” I’d protest, “left handed is who I am!” But—I live in James Horner’s world. How could he be dead? How could this part of me disappear? I know that the music is still here—but the idea that there was someone out there in this world actively creating this music, this magic…It reminds me of something I read when Steve Jobs died. I think it was the Onion— “The only man in America who knew what they hell he was doing has died.” The world has lost so much…

One other thought: it’s been heartening to read all of the tributes, to know how many people’s lives were irrevocably changed for the better by this artist’s work. That is a legacy that should inspire everyone. And what’s more—every single story I’ve ever read about him through all of these years, every interview, and every tribute speaks to how kind, gentle, and caring he was. And how genuinely moved to tears he was by the art onscreen, and on the recording stage.

I like to keep my music on shuffle a lot—and I may skip Horner’s music more than any other. Why? Because it’s so evocative, so emotional, so powerful so often—that I have to be ready for it. But when I’m ready—it’s an album I seek. Not a track here or there. Horner wrote symphonies, not songs.

A selection of my writings and mentions of Horner over the years:

I don't know what day it is or what time (October 1, 2006):

A note: Listening, for the first time to Horner's All the King's Men I hear, especially in the first minute of "Verdict and Punishment" the story of Horner's career. It is a fight, an utter fight between him and himself---a fight with himself not to slip into that which he knows so well, not to use his old tools, his old words and styles and methods, his old melodies. It is a fight, there in the first minute. A fight I know, and fear will know better everyday.

121906:

You know what might be great; if James Horner went blind (temporarily, perhaps, but blind). Then he might be forced to write music simply for itself...Not to image. Wouldn't it be a great moment of freedom? From image, and likeness? Perhaps I shall write a short story about it...

A new year, and what's next? (Feb. 7, 2007)

I must give James Horner some credit here, for writing music which expresses that wilderness spirit of boy-hood wonder and communion. I must give him credit for it, because it is music that matters.

And we have this discussion again, and it is an important one, of form over content. Don Davis vs. James Horner, and Newman somewhere in the spectrum between. Is it more important to explore the craft, or to craft something worth exploring? That is, is it important to try new things and test the waters of expression, or is it more important to use your craft to create a world, or a mood, or a reality which is invoked and involving? These are important questions, and of all art. But I know which ones will be remembered. And maybe that is the final judgment.

BUT, what if you could explore, and by exploration, expand your abilities to create a world? I must. I must try.

______________August 2007:

"When a writer has found a theme or image which fixes a point of relative stability in the drift of experience, it is not to be expected that he will avoid it. Such themes are a means of orientation."

---I.A. RICHARDS (think of Horner)

________________Sept. 29, 2007:

I do not know what will come of any of it, except for the future. The future will come of it. I am not listening to Horner as I once did---I can't. And I am reading, now, Fitzgerald, and Austen, and discovering the power of the most literary film series, Lost, and it all is connected together into what will be. Fall is coming on, the wind is changing---there is color on the ground, now, and it is not fall in all its beautiful death. It is life, living-color, and I am seeing the world as possibility, and I have bought paints and tomorrow I shall paint again---I am seeing the world, in images worth taking pictures of---I am seeing the world as something worth exploring again, and it is exciting.

_______Monday, Monday, Monday, October 15 2007

I respect a writer with long chapters. To have long chapters, to be able to see the long-view, but to be brilliant word for word, sentence for sentence---colorful and of that genius and freshness of Thomas Newman, of the length and breadth and depth of Horner---that is the ideal, the standard of excellence by which I must measure myself. And it is hard. Damn hard.

_____________________April 23 2008

More musical connections: The wave-like pulse in Horner's Titanic, especially in "Southampton" at 1:45, is strikingly similar to the opening bars of Richard Marx's "Right Here Waiting for You."

_________________June 12 2008

"Horner is second to none at capturing hopeful optimism that sears with hints of slow tragedy..."

-Chris Mceneany

__________Wed. June 18 2008

In New Jersey now, catching up on my life. For once---I have TIME!

Wrote probably the best thing I ever did on the piano---wrote it yesterday and have perfected its play today. It is quite simple, and only about a minute and thirty seconds long, but it has a clear development and a great deal going on at once---very complicated in its simple way, at least to play---at least at this stage of skill. I don't, however, have a clue what to call it---to call it The New Armistice is creative murder---to substitute art for commerce!---and to call it variations on Scarborough Fair is somewhat unfair---both to myself and to Horner, whose minor theme from Land Before Time finds a place...And so I have called it, simply---Variations on Solitude, as I am alone here, and it is fine, for this time---something like a little vacation…

_____November 5 2008

President Obama

Vice President Biden

What do I think about the possible? What do I think about this great, incredible, historic moment? Sad news tempers it---for Obama, the news of his grandmother's passing. For me, the news of Michael Crichton's. Michael Crichton: in the end, he may be the single writer who has most influenced my thought. Alongside James Horner, he has been there at every moment of my life---he has shaped not just what I think and what I think about---but how I think. He is the supreme example of the independent mind at work. The independent mind---something which we all pretend to champion, but what kind of independence?

______________ Feb. 6 2009

“I kept telling Terry, ‘Terry, this doesn’t have any emotion in it---don’t you understand?’ And he’d look at it, and he would say, ‘I don’t know if emotion is important here.’” ---James Horner on Director Terrence Malick of The New World

_____May 01 2009

On Wednesday I had to be up early for an event in DC, and so I returned home and at 4:30 or 5 o'clock I went to sleep, exhausted...I let myself sleep and lie sleeping, and how often do you let yourself rest? I rested, and in my rest I dreamed but at some point, when the light was still soft outside, I awoke...and I wrote, to Horner's Iris, in a slanted hand in a sheeted notebook in the gloaming…

________Sunday December 6 2009 - 1059 pm

Ice outside, snow early and my hands are hot on the keys. The computer has been on for too long, and too little has been accomplished. What have I written here, where has my mind been? I have felt lost for a time---have I lost my mind? Where have I been, here on the page, my mind working in words without a page, in ideas without grounding---”grounding” Horner says: “grounded.” He wanted the score to Avatar to be “grounded.” The visuals were so avant garde that the music had to be grounded---it had to be accessible. No weird scales, no truncated rhythms; not too many, at least.

So, how accessible will your work be? Where have you been, where has your task been? I have been away for too long---always I stand away too long, wander from book to article to picture to program---knowing not what I seek…when what I seek is the blank page. A page to speak.

________________1 23 2010

Dream: A movie. The protagonist, who is me---or my character---is a little boy, six or seven years old, with a white frock of hair sticking up. The boy is being made fun of by an older child who nonetheless is in the same grade----these two have been cast in the same grade, and there is a scene here, taking place in the cubby-room where coats are hung and the class has just come in from the cold. The walls are dark and green, the lighting soft and the air thick with the smell of luggage and leather. The older child is making fun of the protagonist, and he lifts him up and hooks him by the back of his jacket against the wall of a bathroom stall, and then grabs his hanging feet and sets him swinging back and forth like a pendulum. I can’t help but laugh at the feet---but there is a sliver of magic in our protagonist, and in a blink we’re shot out of the room like a firework flare and out across the distance, into a country nightscape----and suddenly I’m walking down an old country road with Jamie as we watch this movie, the stars are out, the distance is studded with hills, a lake, quiet houses, waving grain; the air is aromatic, the wind whispering softly, and we’ve been transported into the past; we are walking towards an old castle, Warwick Castle, and as we walk through the night James Horner’s score to The Spiderwick Chronicles plays, slightly ominous and creepy---.

We walk on; out across the distance of hills and dark houses a shock of light bursts into the air, a firework going off miles away---the landscape pulses a soft blue and the flare thins out, reflected laser-like across the small pond. I point towards it, to show Jamie this lightscape, the realness of the image; and in that instant the sky above crackles with silent bolts of lightning, sewn through like glowing string. We pass through the silent grain, beyond the log fences and down a widening hill, where the path wraps out towards the castle walls---when another firework bursts ten feet away, purple sparks falling skyward---from somewhere deep inside the cornfield. Jamie is startled, but I’m unperturbed---except by the implication that there in that spot someone has set the fuse. We do not who he is. As we move down the slope we come to a small stand, four poles and a tent of white cloth---where an older, bonneted woman and her daughter serve pewter mugs of hot tea and milk. Jamie takes one, I take another, pour a bit of milk from the heavy pitcher, and we stare out across the sky---it’s completely transportive.

Look at the stars, I say; don’t they seem real? Here is a movie, almost better than Avatar---don’t you feel like you’re here, like you can explore this space? But in the rounded globe of horizon and sky I can see that the stars are close, projected as onto the inside of a sphere, like the rounded, 10-story edge of the Cinedome; I can see splotches on the screen, and the lines of panels. Then, without warning, a square screen is projected onto the sky over the landscape, a twenty-story screen with red-white-and-blue edges, where a film is played---we see our characters, the boy with white hair, the class of kids, a split-screen montage of the children in jackets, walking out across a lawn of wet grass, strewn with wet leaves---the trees are brilliant, red, gold, orange,---an earlier scene taking place in fall. And against these images, music plays---a triumphant, symphonic piece, horns wavering, chimes rising, I hear the music---and as I wake, I hear it still.

I hear it now, as I type: In the dream I had thought it was the end of Sibelius’s Symphony No. 2, but now I know it is the transcendent moment in Horner’s A Dark Cloud is Forever Lifted from The New World, at 5 minutes 15 seconds.

____________Monday April 26 2010

Listening to Shostakovich, searching for a theme from his 5th Symphony which many say was stolen for use in Horner’s Troy score. So far I hear little resemblance in either the 1st or 4th movements. I am listening towards the center, but as I do I reflect on two statements of Horner which are---I believe---in contradiction:

Half of the time he states that he approaches each film score as an opportunity to write a serious piece of music; instead of a requiem mass, he would write a score to a gothic film; instead of a string quartet, he’d write a score to Iris. There seems to be truth in this, as there is to his likening of each score to the building of a ship.

But the other half of the time he says that there is more to it than that; his interest and passion for film scoring is not simply a means to generate an audience, an income, and perhaps what’s more important, the budget to hire players---it is more personal than that; it is rooted in the very marriage of music and image. Horner noted that in seeing a film with music he was moved with such profound emotions that they resonated out beyond the theater, they stayed with you, transformed you, so that you were a different person when it was over; he contrasted this with attending a performance of Beethoven; he took pleasure in the music’s architecture, its brilliance, as well as its sharp execution, but that was it; when it was over it was over and you left the theater and continued your daily life. He found in film a connection, an emotional resonance in music that had been lacking in his own experience with music---including his own music.

Which can lead us to see why he says that a project that does not emotionally move him does not interest him; and serves to explain why he is always denigrating the latest blockbuster---even though he scored the two biggest blockbusters in history. And shows us why he has not composed more music outside of the theater, or premiered or performed more in the concert hall. His musical experience---and the way he values music---seems to me profoundly different than John Williams---a virtuoso who I believe uses music to express movement as well as color and emotion. In many ways, Horner writes a kind of musical poetry, while Williams is the consummate prose stylist.

****

And now we have reached the third movement…and it begins to sound familiar, but I am not so sure that familiarity is with Horner. No, it is with Horner---but the track “Greer’s Funeral” from Clear and Present Danger, a track which I never had much patience for, and which---for its bleakness and lack of color, quite thankfully has seldom been repeated or expanded upon in Horner’s repertoire.

****

While this distinction of Horner as poet and Williams as prose may seem odd---after all, isn’t Williams the more inventive and isn’t invention the place of poetry?---I think it is clear if we consider poetry primarily as a medium of the senses and of the heart, and consider prose a medium of the mind. Poetry is a reverie, a sweetness, a meditation; prose is an exploration---and these are very different activities. There is a structure to poetry because there is a clear and definable purpose to it, while prose, as any true investigation, can lead in many directions and down many false paths. Prose is more prone to unevenness and flashes of brilliance…where poetry is a song, prose is a symphony; large, disjointed, difficult in places, sweet and demanding; it wants to be compelling. Whereas poetry wants nothing more than to make you feel. Prose is interested in itself and its own brilliance, in showing off its inventiveness, poetry in helping you to feel. Yes, prose is interested in finding the Truth---maybe the objective Truth; poetry in finding your own Truth, in feeling. And so it is with these two composer’s music.

The issue is not black and white; but Horner’s music does exhibit a certain logic to its structure, a one-way quality that makes you feel that you are following down a path which has been laid before you, carefully and with some purpose---it moves, usually, in a straight line from beginning to end. Williams’ music is more multi-dimensional, more cerebral, certainly more brilliant, but perhaps not of a greater genius---because while Williams has a facility for penning catchy themes and melodies, Horner may have a greater facility for catching the human heart. Williams has great powers of inspiration; Horner, of reflection. Which is more meaningful?

I can only answer for myself; I recognize that Williams is a greater musician---I know this. But it may be that Horner is the greater composer because his insight into the human heart, it seems to me, is purer and less mediated by conscious intention. There is a grace and elegance in his writing, a true affection, a quality which is transcendent not as religious aspiration so much as personal meaning; Horner’s music is of the soul finding fulfillment in itself. Williams’ music is not of the soul, but of adventure and outward striving, force, motion…He can write love themes of extraordinary beauty, but more often than not, it is an external beauty; one which is not the song we know we hear when we close our eyes in silence, but one that we hear on the radio, or the CD-player, or even in the concert hall. I have said before that Horner has a skill in writing themes and music that seem to be universal; he can write this year music that sounds timeless, like it’s been around for centuries, like it’s right. Simply right. It is stripped, then, of the recalcitrances and ambitions of much of music as music…not music as music only, not music even as communication, but music as communion with that inner landscape of the soul, beyond all striving, which seeks yet for fulfillment and meaning in itself.

***

I have listened to all of Symphony No. 5 and none of it reminds me of Troy except perhaps for the repeating notes at the conclusion of the 4th movement, but these are not at all like the discrete repetitions employed in Troy. How could people confuse the one with the other? They must be thinking of some other Symphony, because it simply isn’t here.

EARLIER NOTE: I don’t hear Shostakovich in Horner so much as I hear Prokofiev in Shostakovich. And, to a lesser extent, Mahler.

_____________July 15 2010

Dream: Listening to an audio review of James Horner’s The Perfect Storm. Christian Clemmensen of Filmtracks has a version of his review that you download as an MP3, which plays over a track of the music and includes his comments and thoughts upon it. I am listening to the final track, which is very long---and he is saying that the music is repetitive in its statement of the theme, but Horner deploys subtle variations and musical devices as he restates it, inventing new musical movements to keep the melody fresh, though always---familiar. However, as I am listening to this I am standing on a platform in the center of the sea with Jamie---and something is about to happen. A tidal wave is on its way, and we must hurry to seek shelter. The platform is a wall---about four or five feet thick running thirty or forty feet high---with a walkway on either side and an arched entryway, like a drawbridge on the palace grounds of some empire. But there is no empire here, only the wall and on either side, the sea. But there, on the side further inland there is a small contingent of boats, over which is constructed a platform of wood forty feet tall. I hurry to climb one of the pillars to this platform, but the beam folds in under itself and I must balance very carefully and take risks, reaching out and pulling myself up and onto the balcony---where people have gathered in anticipation. Someone asks me-- “How will we get down?” I say: “when the water’s here we’ll just dive.” And so we wait, standing there where the wind blows our hair in that salty, sticky anticipation---waiting for the wave to arrive.

_________March 25 2011

Last night you were thinking about how nice it would be to spend a few minutes to design a large, coffee-table book filled with Christian Clemmensen's reviews of Horner's works---on one page the review, on the other, a photograph or two from the recording sessions and the film itself. It would be a fine book to read and to have, and it could begin with an introduction by yourself, and something of a conclusion you could write. That would be an interesting project, but print is dead, no? And I began thinking about how a book like that, on heavy paper and glossy color prints, was a product all its own, independent of any computer screen, there to stare at you and implore you to read. No iPad app could do that.

___later (in the evening):

This morning I was thinking more about that book, the compendium of reviews on Horner and how I might like to write an introduction to it. I was thinking how nice that book would be to have in hand, to grab it off a shelf and read through it as I listened to my favorite album by Horner...what format could be better? Certainly not an iPad app...but then I thought---well, of course there’s something better, because we’re talking about music here...and music is all about sound. And so I thought once again the thought I had in the dream so many months---maybe a year ago, where I find myself listening to a review by Clemmensen that is in the form of a podcast. The review can weave in and around and incorporate excerpts of the actual music itself...and what a strong medium that would be for music reviews, especially of music that is so textured and orchestral. Well, then I thought---why not do it? I have forever resisted the impulse to write down how I feel---really---about my favorite composer, because what words of mine can compete with this power and beauty? But context can lend appreciation and it can help you to hear anew.

Anyway, it would be a fun project, and in the end I’ll have produced something of great value---at least to myself, and what else matters? I write poems and stories and paint paintings to mark the birthdays of friends and family, why shouldn’t I do something for myself on my own birthday? I think I will; and I think I’d like to get into the habit of having a special project to give myself as a gift on my birthday. So why not try it, attempt a 30 or 60 minute appreciation of Horner’s music, weaving in and out and around excerpts and pieces of his work? The problem won’t be doing it---I’ve done audio editing before, that’s not a problem at all (although I anticipate that getting the right timing and transitioning in and out of multiple pieces may be tricky)...no, the issue really is one of form. What form will this take?

There are the obvious forms, and I have here in my room Conrad Wilson’s thin volumes on Mozart and Beethoven---”20 Crucial Works.” That’s an idea, but an easy and maybe in the end too gimmicky one. To list 20 crucial works, although yes, it would simplify things. But try to be different. His pieces were adapted from programme notes, and he had a strict form to adhere to; he had to discuss the composer’s biography, where and when he was when he wrote it, where this piece fits in his and music history’s development, important influences and notes on past performances. But I don’t want to get into all of that; all of that is extraneous to the matter at hand: music. What it means and what it does for you. What Horner’s work as a whole represents---the breadth and depth of it.

I want what I write to this music to be deep and poetic and wise...and yet, also, fresh. I have here a list of attributes that might be worth mentioning:

- Power/Force-Brutality

- Soaring melody

- Nature and Native American influences

- Home

- Action

- Love

- Bells

- The human voice

- Irish music

- Creepy/Nacht Music

- Connections (4 note motif, shared themes and developments)

- Horner may use the most new/distinct sounds of any composer

- Extraordinary moments

- Long pieces

- Whole albums

- Differing instrumental pallets

Formats include:

- Top ten albums

- Top ten tracks

- Crucial developments

- Extraordinary musical moments (either stand-out moments or bits from each album)

- Dividing it into the essential evocative areas - home, love, action, distance, inevitability, darkness, hope/joy

- Touching on all of these things, mentioning all of them...but organically...

Will it include quotes by Horner? One way to simplify it, as you are trying to figure out voice---I mean, who are you talking to, are you speaking from personal experience, I hope not, that would be boring, boring to listen to and it would get in the way of the music...but one way to simplify it would be to assume this is a kind of speech. That would simplify and focus your language, at least...

Another way — just write it organically. Begin by asking this question: Where do you start with James Horner’s music?

If somebody asked you which album to start with, where would you tell them to begin? Doesn’t it depend on the person? What was it for you? The first one I heard was Land Before Time, although I didn’t know it was Horner at that moment. Then Fievel Goes West, that “Somewhere Out There Song” which we sang in the school play; then it was probably We’re Back, a Dinosaur’s Story and finally, in 1996 it was Titanic and the first time I really heard him and knew it was Horner.

Thinking of it as a speech is too conventional, though, when you can use sound design imaginatively, use the music itself to tell the story, rather than try to tell the story of the music.

One thought was to make it a kind of fictional Q&A between yourself and Horner. So many interviewers have failed to ask the essential questions about the music itself, rather than the process. The music and why, why this music? Why that instrument for that moment? Why a theme of that many notes? Why is it good? What makes a good piece? What is your favorite piece? Which is your favorite to score? Favorites tell us a lot...

Horner is your favorite, and it is time now to explain why. In doing so, maybe you can get closer to understanding what makes artistic greatness, what makes something better, and what is beauty?

You can see Clemmensen struggling with this question, the question of form and structure. Do you go track by track through an album and risk missing essential comments about specific themes, or do you go thematically, picking pieces up from multiple tracks and following their development? Personally, as a listener, at least, I find it more useful to read a review that goes track by track, since it’s a bit much to jump around and find the places the reviewer might be talking about in tracks 3, 5, 6, 8, and 14.

You could talk about the first tracks of each album, and the last. The start is very important...

And of course the one thing you have not talked about at all are the movies themselves, but those are secondary to this discussion, as is Horner’s personal history...That’s all been talked about before. Here I would like to focus on the music.

Is this an introduction or an appreciation? You shouldn’t just touch on those obvious parts that people are going to already know, you should highlight hidden colors and moments.

The difficult thing is that of course this is not definitive; it couldn’t be, not for someone who has written more than 100 hours of music...it’s not a summary of his life’s work, it’s a celebration of its special depth, breadth, power, and beauty.

Try to think of what you would like to listen and then, try to top it:

BEGIN:

From silence...there is sound. It begins with a pulse or a beat or a blast...but it begins...and a new world...dawns...

NOTE: perhaps this isn’t strictly about James Horner...maybe it’s about music in general, but it is narrated by James Horner’s music...

THINK about where the music puts you, where do you see yourself, what place do you find this music? What does it say? What makes it sad or happy or dark or brooding? Paint with words, if you can...have fun with it...be surprising. And innovative.

Maybe your mistake here is that you’re trying to be authoritative. You’re making the mistake of the non-fiction writers you despise, trying to think up your words and reach your conclusions before you arrive on the page. That is folly. It’s false dramatics, all of it. But there is a real drama here, and the drama is what you’re writing right now, this attempt to understand this music, to make sense of this composer and what it means to listen, to answer the question:

What is that sound?

Make it a dramatic dialogue between yourself and the music...make it live...

Don’t be explanatory. Explore.

Make it a movement from darkness into light...from confusion into clarity...from ignorance towards wisdom and understanding...the struggle must be real...Imagine yourself a botanist or scientist, whose first and only time exploring the forest is alone, in darkness, as the Earth behind and beneath you falls away---you must move forward, but you must also understand in order to follow the right path to the light.

______April 14 2011

Rhys Owen Cromwell is born. And I must write something to commemorate this day - this day in which the Titanic sank, 99 years ago...By chance I happen to be listening to Horner’s Titanic...but neither of these momentous occurrences are the reason for my writing in this this late evening. I just wanted to note a thought I had driving home late---that all of the great people I seem to admire always seem to be the less obvious among their contemporaries. My favorite Kennedy is RFK, not JFK. My favorite composer is Horner, not Williams. My favorite author is RPW, not Faulkner or Steinbeck or Hemingway...I admire Ford Madox Ford, not his partner Conrad. I always liked Biden more than Obama. Does this say something about me, or does it say something about the nature of success, talent, and excellence? I wonder if in some instances it might say both...and more.

________August 27 2011 (Hurricane Irene day...)

There was something in Horner's conclusion that with Avatar's planet presented as so visually new and exciting, the music in some way had to be grounded; audiences maybe weren't quite ready to see revolutionary visuals alongside revolutionary music---they needed something to hold onto...and the music served that purpose...Except, I really wanted to hear something more revolutionary from Horner.

_________Sept. 6, 2011

Leaders. Aren’t these so few and far between? Even in industry, in business---who do you have? You have Steve Jobs, yes; you have...well, who else do you have? Who else is defined by quality in everything they do, in the vision to get there, the personality to inspire, and the management acumen to organize the energy to get there? Maybe, again, you have Generals like Petraeus? Directors like David Fincher. Maybe composers like Horner and Williams, when you think of consistent quality and the ability to organize a team to achieve it...Bill Clinton I think had all of the necessary qualities except maybe the discipline and the vision, but these are key attributes...I still hold that he’d make a better president today than he made in 1992. I don’t know...there really aren’t a lot of great examples of leaders that I see out there; could it be that this world, this culture is lacking in great leaders? No. You just don’t see them; they must be there---your spheres of knowledge are simply too limited. Look at sports; surely there’s a great example in sports you are missing...and internationally, in other sectors and industries.

___June 27, 2013 - 5:45 AM and this is true at first light:

I've listened to Horner for so long, and there is the main-line, the main theme, that everybody hears and enjoys, but then there are these little tiny moments, these nuances, a brief horn solo here or there, something small like that, or something in the grander plan, in the architecture of the piece itself—that maybe only ten people will ever notice—or maybe just one—but it's incredible, and it shows how much thought and love went into it, how much beauty.

___________________August 21, 2013

Weather happens in the clouds, it's true. But it also happens in the air we breath, and in the movements of our lives. When James Horner was composing music for A Beautiful Mind, he described the thoughts moving through John Nash's mind like fast-moving weather systems. I like that image, but I think it's limited. Because those weather-systems connect with other minds and other patterns to form a climate or a season—weather phenomena that aren't so fast-moving, but which roll across our lives in waves so big that their start and end is almost imperceptible. Who can say when Summer truly begins? Or when Winter ends? Who can be so sure?

__________September 1, 2013

Music

James Horner’s wife is a painter. And he uses metaphors of painting all the time, in talking about his own music. As a composer working in film, the music always begins by watching the movie. He watches a rough cut, trying to get a feel for the sound of it. He wonders: what kind of mood or color—what kind of place—does the movie put him in? What does he hear? With the film Glory, about the Civil War, he saw the horror of it and the sadness, but also the innocence of these soldiers trying to do their best for the country. And he heard a children’s choir and tolling bells. Now, with the orchestral colors chosen, he began to paint. But it all starts with the color, with a feeling—and he slowly builds a world around that place.

This isn’t how every composer writes music. Some look at each scene individually. Thomas Newman, for example, works this way—and so his albums are all comprised of short 1-2 minute tracks that are fun and energetic but begin and end in a single instant. They’re like flies with short lifespans. As a result, his albums are hard to listen to all the way through, because they’re just random collections of scenes. There’s no cumulative effect—no sense of permanence. Horner’s music is different. It’s rooted in a setting. And the sound of each album takes you there, with each track an exploration in a new direction—but in the same place, the same color palette; part of the same work of art. The pieces, like paintings, fit together to tell a larger story. When you listen to a Horner album, you don’t know where you are inside of it—each track bleeds into the next and you get lost in a new world. Music in general has a special power to take you places. But with his music in particular, the places seem larger, more expansive. Over time, I’ve come to know these places like they were in my own backyard.

Place is important to me. But places, like people, are often so fleeting... And whether it’s us going or them going, the effect is always the same: we feel a little bit lost, a little bit shattered, like a piece of us is missing and we can’t get it back. Stranded and we can’t go home.

Which is why, for me, music is so vital. Horner creates whole worlds that I’ve come to know and love and explore—and these places are as true in my mind as places I have lived. But these places, unlike all the others—they endure. And no matter what happens, no matter what or who falls away, my music is always there. Welcoming as it’s always been—willing always to take me home. It’s a place of peace and openness, a place of warmth and understanding, a place of tall mountains and swaying trees, of fullness and distance. It’s a place where I can forget myself and simply see life as something beautiful to enjoy.

In a life of so much change, a life where most of the time I feel like I have no true home, I have felt so thankful to have these places, this music that I can always return to, where I’m always welcome and I always know I can find warmth and fullness...So much in life is fleeting, but having music has kept me grounded. If I lose everything, I’ll never be lost because I’ll always have this.

________November 25, 2013

And so you see, even in these difficult circumstances, I can hold onto who I am—and, what’s more, take that “who” to new places, new heights. It’s like what Horner did with Legend of Zorro—he used all of the same themes, but remixed them, cleaned them up, orchestrated and filled them in with new colors to make it resonate deeper, richer, newer than it had been before. That second score is better than the first because it’s no longer about about asking: what is the theme—it’s about asking; where can I take this theme? I’ve moved beyond asking: who am I—now I can have the freedom and the fullness of possibility in asking, what can I do with this gift? Where can I go, where can it take me? We’re going to new heights, now. And there is no limit.

_____________December 3, 2013

These last two days have been pivotal in the true sense of that word: a pivot. Last night, a random shuffle of music late in the evening reminded me of James Horner’s Black Gold score—his most recent release and one that I never truly got into. With the heaviness of sleep closing in, I decided to listen to that album as night music—a very odd thing considering it includes some action music. But I listened, and I loved it. Today, I awoke and played it all morning. And I’m playing it once again, now. Marveling at the new textures and the care he put into every single note.

In one of the Frank Chimero’s essays I read today, he talked about care:

What is good design? I’d say as an internal pursuit, it means saying things that you believe to people that you care about. My best work always springs from that situation. From an external vantage, I think it looks a lot like life-enhancement. Good design is meant to help other people live well, and if it doesn’t do that for the audience, there’s no point in it existing. And the funny thing about that is both of these successful outcomes spring from the same thing: caring more about what we do.

------December 10, 2013

I was in my car—and that’s where the idea started. I was in my car, driving along El Paseo, marveling at the deep textures and bass of Horner’s Black Gold...

Monday, May 12, 2014—

On Saturday, I heard James Horner’s “Flight” music at the Pacific Symphony’s Segerstrom Concert Hall in Orange County. As part of a program featuring the work of film composers in other mediums—mediums beyond film. It was Naomi’s first-ever symphony performance, and my first here in California. This wasn’t the Kennedy Center, but a new modern structure; and this wasn’t classical music—but the music of living composers. There were quite a few things I noticed on hearing Horner live:

- The fullness of his orchestrations: Horner’s piece was played third in the program and just after the intermission. The first piece was the Williams work: “Tributes! for Seiji,” which was surprisingly unmemorable—dancing as it did from section to section in the orchestra, but with no true center. The second was the rambling and ineffable work of Howard Shore— “Mythic Gardens, Concerto for Cello and Orchestra.” It was made for a smaller orchestra and was all of one color—with one minute passing indistinguishably from the last. All told, it came off as rather soporific—but that may have been the result of a missing piano. For some reason, I think there was supposed to be piano accompaniment, but this performance lacked it. Horner’s, in contrast, blasted us forwards with a full and rich performance. The whole orchestra played as one instrument, with deep, full-bodied tones that you could feel. Whereas Williams’ piece seemed like a crafty demonstration of orchestral refinement and Shore’s piece was a small poem—Horner’s was a symphonic statement. Interesting, though, that Shore tried to capture these gardens while Horner tried to capture the wonder of flight—and how their passions led them in different directions.

- The melodic quality of his writing: The work of every other composer in the program, including the dark, brooding symphony by Eliot Goldenthal, seemed to play with notes but without any melodic core. Shore’s work had a center—but that center was a feeling and a tone, not a melody. Horner’s melodic writing spoke in a different language—a language that each person in the audience could understand. Where the other pieces played with sounds and tone, Horner’s communicated in a language of feeling that you couldn’t help but be moved by. The reviewer from the LA Times complained that the piece was too much like film music and that it repeated its simple melody “to death,” but it’s exactly this thematic quality that makes the piece not only accessible, but enjoyable. I agree; the first time I heard it, I wished for fewer repetitions and more development of the theme—but on multiple listenings, you do notice subtle variations, if not in the actual notes, in the orchestrations and the handling of those notes.

- The incredible use of the French Horns to create an otherworldly sound that I thought was electronic in the recording: At around 8:14 in the recording, there’s a repetitive cycling of sound that I was almost certain had to be created electronically. In person, however, I was surprised to see that this whirling could be accomplished with the horns in such a sustained fashion. It creates an incredible atmosphere—although it’s unfortunate that some of the tinkling sounds, which are electronic, couldn’t be reproduced with an array of triangles or similar percussions.

- The difficulty of playing the horns at the moment when they play out of phase—and of keeping a sense of cohesion to the same extent as the recording: The disjointed horns that play at about the 10:20 mark in the recording was a true challenge for the players in this orchestra. Although they did a good job of sounding disjointed, they lacked the inherent sense of cohesion that you get with the recording. This reinforces some of my other experiences with other renditions of Horner’s work. While the writing may seem straightforward and less technically complex than the orchestrations of someone like Williams, it’s actually very, very hard for an orchestra or a conductor to reproduce the smooth transitions and exacting counterpoint of Horner’s recordings.

- The grin on the face of the conductor: With my seat high and behind the orchestra, I was able to see the face of the conductor. While conducting the other works, conductor Carl St. Clair looked alternately focused and determined, but during Horner’s “Flight,” he had the biggest grin on his face. It looked as if both he and the orchestra thoroughly enjoyed the change in tone.

- The loudness of the final note: One of the greatest joys of seeing a live orchestra is when it gets loud enough to shake the room. The only time that truly happened on this evening was with the final resounding note of Horner’s “Flight.” It was a fully satisfying conclusion to what was clearly the highlight of the night.

____________Sometime in 2014

IDEA FOR A TELEVISION SERIES ABOUT FILM COMPOSERS: (Note: you had this idea inspired by the track "I Want to Go Home - Forbidden City” from Horner's Karate Kid) Present an exciting scene from a movie (ideally one no one has seen), and engage a series of composers in the act of creating a score for that scene. You could do one scene per episode, OR, instead, you could focus each episode on one composer, or have this building across the entire season. So that in the first episode we see the scene and meet the composers. Then in the second we follow each composer as he or she discusses the scene and tries to figure out the themes.

THEN we watch as they explore the orchestral colors they want to employ. And then we watch them contract with the musicians they need, pulling whoever they want in, and using the studio orchestra as needed. Then we see them developing and spotting the scene, including what kind of feeling and emotion they want at each moment. Then we see them begin work with the orchestra, introducing themselves, getting to know the players. And then we watch as the pieces are recorded. We're there along for the whole ride. And finally, we get to watch the scene with the music and decide.

ALSO: You could have them consult with other composers in history. And spot different musical inspirations…calling up the orchestras to play the music of people they are inspired by…The key: to have many different approaches to the music of a scene. We should also look into someone creating a song for the scene, one that's spoken with words, so they have to contract with a lyricist and maybe get a famous performer to perform the track. Someone who has an electronic approach. Someone who has no themes. Someone who has great propulsive movements (like Newman). Someone who has soaring themes (Williams) and someone who has a refined and integrated approach (Horner). NOT these actual composers, but different musicians and composers.

ALONG THE WAY we can learn about the different pieces of music, the different techniques you can employ with an orchestra, the variety and diversity of musical sounds and expressions possible, and what these mean when merged against picture. Put it all on an album at the end.

ALSO: make it possible, if this is a web series, for people to decide HOW they want to watch. They can follow one composer's journey with the music from beginning to end…OR they can watch hour-long episodes that follow the four to six composers as they move through these various stages. So you get to decide whether you get one biography. Or a book more like Team of Rivals each episode.

NOTE: The problem with having the audience vote is that in the end they'll vote according to which PERSON they like more, vs. which music they like more. So perhaps instead of having viewers vote, you should pre-record and have people who do not know these performers vote on the film based only on the sound of the score… Perhaps this group will include the writer and director, as well as audience? Maybe it's the director who has final say, but then wouldn't the composers just want to learn about the director and his or her tastes?

NOTE: Shouldn't the piece, rather than being a big-budget film---shouldn't it be one scene from a student film that is actually being funded by the proceeds from this television show? What you want: access to the studios' audio collections and rights to show some of their music on the air if it's mentioned by the composers…And participation by some active composers today… If it's a big-budget movie, or a film from one that's going to be big-budget, then you could really create some buzz for the picture, and it would be fun for viewers to see how the composer expands on his or her themes at the big box office.

AFTERWARDS, the team could go touring around the country doing concerts with a symphony.

________Sometime in 2014

ASK: What would your life be like if James Horner didn't exist? Or didn't write music? Think about how different things would be. Would you even be a different kind of person? Would you be less at peace with the world? Less open to the beauty of nature? Would your horizons be more limited and emotions more stunted? What would fill this silent space left by his music? Someone else's music? Would music mean as much to you today? Because there are things that his music does that no one else's music does…

_______________Tuesday, May 26, 2015

Pas de Deux. Horner's new concerto. His first serious concert work since beginning his career in film. The piece is a revelation. I have been following his work for most of my life, but I never knew he could write something like this.

The piece is full of emotion and color and the summery breeze of something real. Something felt. The orchestra vibrates with a kind of living energy, as if it's shifting and turning—like waves in the ocean. Diving and cresting to their own momentum—and yet, from afar, shimmering all together in colors bright and surprising. This is not the commanding hand of a John Williams or John Powell—this is not the pulsating rhythm of a Don Davis. Here, yes—here is someone setting the orchestra free to find its own voice. It's so interesting to consider—but listening, it's absolutely evident that the piece was written by a master of the form: and yet, it's not at all about that mastery. It's about the mood of the music itself. The music itself is speaking here, not the composer.

Listen—listen! Listen to what the music can do. I have never heard music like this before.

My feeling, on listening, was a feeling of tremendous gratitude. Here is a piece, so rich and full—it is a forest to explore—like a wooded glen close to home that you just know at any moment will be there for you to wander in—at any moment, for the rest of your life. I know that each time I visit, I will see something new. Here is nature, and all that I love in it, handed to me as a gift.

The piece moves in and out of phases, like a landscape on a cloudy day, moving in and out of sun and shadow. The clouds are dark but their edges white—the sun bright but its shadow black. The air is clear, dew sparkles, and the life of the forest swirls around you as you wander.

There is the familiar—short bursts of movement that I've heard before. Or the drifting scent of air I've breathed —but it's there and then it's gone, transformed. A glimpse only—faint reminders of joys past.

It's so gentle. The world is beautiful.